To be a pilgrim is to be connected. We are all connected, we are all related, there is no I and the other, I am the other, the other is me – that is what makes me a pilgrim in life and a pilgrim of the Earth. My pilgrimage is not going somewhere; my pilgrimage is to be one with the universe. I am the universe, the universe is me.

Satish Kumar

I spent all of May – the queen of months – drawing in France.

The invitation to the residency near Albi (my second), could not have been more timely. Leaving England at the end of April, I was burnt out and bored of myself following two years of intensive work for my second solo show in as many years. The hill-top hamlet I was headed for is deeply rural, and profoundly quiet. Set up and maintained as a restorative retreat for invited artists, there is nothing there but a huge studio, a small apartment, a flower-filled garden, hens for eggs, and a pool for the heat.

The place is a wildlife paradise; carpenter bees, hummingbird hawk moths and all kinds of butterflies crowd the garden and surrounding meadows, (France has around 47 species of fritillary alone), kestrel and hen harrier quarter the wheat fields, while above them kites and honey buzzards describe never-ending thermals in the blue. Woodpeckers, cuckoos, shrike and nuthatches are all commonplace. Nightingales sing day and night in the spring, and hoopoes and swifts nest in the courtyard walls. In May the fields and verges are waist-high with wildflowers. Late into the long evenings the lime tree hums with bees and the scent of honeysuckle fills the lanes.

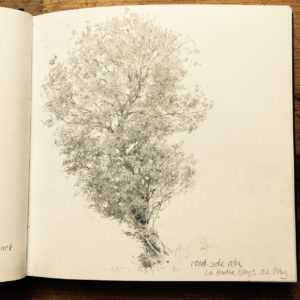

This gift of space and time is one month long. Towards the end of my stay, an English visitor asked me if I had ‘achieved everything I had set out to achieve’ during my stay? The question threw me and my blank look prompted a further, ‘Well, I mean, did you have any targets?’ I had, I realised, almost nothing to show for the month. I’d read a box of books, not listened to the news once, gained half a stone, and spent most days either walking or staring into space or sat under a tree drawing in small sketchbook. No ‘target’ had been met, nothing finished, ‘achieved’…and yet the time had been invaluable – beyond price or measure. Something had healed, the ground had shifted, something was definitely clearer.

Early in the month I read, In Search of Grace – an ecological pilgrimage by Peter Reason. Peter is my uncle and this is his second book describing his journeys in a small sailing boat around the western coasts of Ireland and Scotland. This is not, however, a book about yachting. There is plenty of sailing and lots of weather but much more than that it tackles huge ecological themes and asks how a shift in our spiritual response to nature might support the pragmatic prevention of the destructive impulses that are causing such a dire state of affairs in the natural world.

I had planned nothing for the month other than giving myself the space to see what happened. Paul and I had a printing press to set up and I had bought copper and tools, vaguely imagining I might make engravings. But reading In Search of Grace was to change and set the tone for the whole month. I read and re-read it, returning in particular to Chapter 2 on the nature and history of pilgrimage. Could it be that pilgrimage has something to do with what I do as an artist? Surely that is too high-flown an idea? And yet it was an idea that wouldn’t go away.

Peter writes; “The English term ‘pilgrim’ originally comes from the Latin word peregrinus (per, through plus ager, field, country, land), which means a foreigner, a stranger, someone settling for a short of long period in a foreign land. Peregrinatio was the state of being or living abroad.”

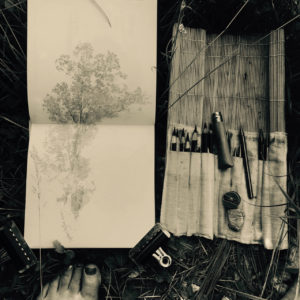

I was definitely not ‘on a pilgrimage’ in France. It’s a country I am very familiar with and I hardly feel myself a stranger there. No, this month was more of a ‘retreat’. However, as the days passed and the month took shape, I found that having left the comforts of my own studio at home I was less and less interested in being inside the magnificent studio there. The desire to be outside, ‘in the field’ was visceral. Could my trips out into the countryside with my sketchbook be miniature pilgrimages? Working en plein air certainly has many of the characteristics of pilgrimage: To begin with, one prepares, (packs water, kit, puts on suitable shoes and so on). One prevaricates, (another coffee, looks at the weather, thinks how much more comfortable it would be to stay home). Eventually one steps out over the threshold, and typically one walks.

“In modern times, the idea of pilgrimage falls within so many cultural and spiritual traditions that it holds no single meaning. However, it usually entails a long journey in search of qualities of moral or spiritual significance, a journey across both outer physical and inner spiritual landscapes. [..] In an important sense the pilgrim leaves the everyday and familiar, and journeys through an in-between space toward some transcendent purpose”

Wasn’t I too, in walking out every day, looking for new insights and deeper understandings? Wasn’t I too trying to disrupt the patterns of everyday life, step away from the habits of civilisation? Maybe I had come to France this time not to ‘make work’ but to open myself to a different view of the Earth of which we are all part.

No! this was all too pompous. I began to laugh at myself; while Peter had had to contend with the massive force of tides and winds, I mainly had to work out how to stay in the shade and not get bitten by ants. A voyaging sailor is at the mercy of huge Atlantic weather systems. He or she is at times in real danger from vast waves, fog and treacherous rocks. He or she must brave the night at sea, understand and master the strong currents and hidden perils of a wild and unknown ocean’s edge. Perched with my sketch book at the edge of a field, most days the greatest dangers to myself, aside from sunburn and wild bees, were decidedly human: a farmer spraying pesticides or the odd weird man in a van, stopping to stare.

Pushing the thoughts away, I read other books, tried to occupy myself with the press but the words of Satish Kumar returned to me; “A pilgrim is someone who keeps their mind and heart open for whatever is emerging – it is that openness that puts you on a pilgrimage, not how many miles you physically travel.”

So, every day I packed a small bag and set off, on my on, out into the fields and woods. Every day I would rehearse a little argument with my lazier self that wanted to stay home and every day I’d go out anyway. It got easier. I became, exactly as Peter described more ‘resilient’. I wouldn’t give up at the first drop of rain. If it was windy, I’d move. I started to know the landscape, which trees offered shade in the morning and which in the afternoon. If the drawing went badly, I’d turn the page and start another. I learned how to walk slowly and then sit and wait for what came instead of rushing to work. I learned that the improbable and unexpected often led to the most interesting hours and ‘better’ drawings.

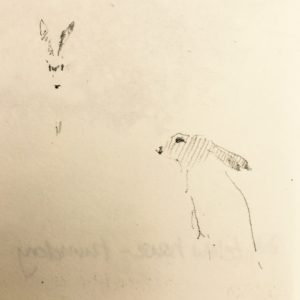

There were too what Peter describes as ‘moments of grace’, moments when somehow the boundary between self and world loosens. The instant, barely-worth-describing, on a hot day, hours into a drawing, when the scent of a horse and the sound of a river met. Almost nothing and yet sound and smell so vividly realised together, after long hours of stillness, bought tears to my eyes. Or another in unpromising rain, very early in the morning, hunched under oaks at the edge of a field, when no less than five young hares appeared as if from nowhere. Closer and closer to me they meandered, until just yards before me they raised themselves up onto their hindquarters, (front paws soft and dangling, black tips to their ears) and looked back at me. Ten dark eyes in a damp hayfield. Twelve with my own. Minutes passed, pencil stilled. Breathing.

You are very exposed working in this way. There are none of the familiar ‘props’ of the studio, none of the familiar excuses of domestic life and none of the distractions of the modern digital world. Your materials are humble; a pencil, a book of blank paper. Nothing you might do will have any value in a world that is almost entirely monetised. You are small and your marks are unimportant. That is the first lesson. The land and air around you belongs to the bees and the hares, to the farmer with his tractor in the distance and the honey buzzard mewing high in the sky over your head. The heat has more of a presence than you do, the rain more meaning. You are invisible to the demoiselles in the drainage ditch and irrelevant to the nightingale in the poplars.

All drawing is a discovery and I’ve long known that the more I can lose myself in a drawing, the more I can let my brain just take a seat behind my eyes the more the ten thousand things will come to me. This month in France, without setting out to, I discovered something else and that is that each drawing can be a pilgrimage in miniature if you take it to be so. If – wearing humility and some determination, you step out on a journey to open yourself to the world and to pay your respects, there will be difficulty, you will be challenged, and you will need skill. If on that journey or journeys, you persist as the poet Gary Snyder puts it, ‘step by step, breath by breath’, and are not afraid of intimacy, you will learn something and, when you least expect it, there may, just may be grace.

In mid-May I made a pilgrimage of the more conventional sort, (for an artist), to the Musée Toulouse Lautrec in Albi. It is a beautifully presented museum and stood before Lautrec’s drawings, with pilgrimage on my mind, I saw for the first time that he too – master that he was – repeatedly left himself behind. Each time he drew a woman, in order to really see her in all her ugliness and beauty, courage and vulnerability he must have opened himself, disarmed himself completely, stepped aside, stepped forth, and in the proud tilt of her nose or the curve of her arm or her tired stockinged legs of course he met himself coming back down the road. Humanity sweet and sad.

I have never felt the desire to draw people. My interest has always been in the more than human world and met in this way – when you go out with just a pencil and the willingness to pay attention, the world offers more than you can possibly imagine. If you are willing to see, it will even reflect you back to yourself. The crook of an oak tree, warm, rough bark, deep in shade, is a corner of your own soul; the ancient upward curving gesture of an ash branch, your laughter; and for sure your life at this moment is as shimmering and uncertain as the shaking of the smallest leaves at poplar tip.

In Search of Grace is published by Earth Books ISBN 978-1-78279-486-8

http://www.peterreason.eu/InSearchofGrace.html

Wow reading that was really lovely. Thank you for sharing all sounds amazing. Xx

I admire both your writing and artistry Sarah. So perceptively delicate yet with such clarity and truth.